Physician documentation can vary in terms of its clarity, completeness, and its usefulness as a...

THE ABSENT ATTENDING: Attending In Name Only (AINO)

Who is the "attending physician"? In the “old days,” the answer was straightforward. The attending physician was nearly exclusively the patient’s primary-care physician, having a long-standing relationship in the outpatient setting. Involvement of other specialties was only required when the care management required skill sets outside of the attending. Patients and their families could expect to interact with a single physician throughout the hospitalization.

WHO IS THE ATTENDING PHYSICIAN?

In the last 2+ decades, patient care has been increasingly fragmented. While many place the blame on the rise of hospitalists, the roots of fragmentation extend well beyond the hospitalist movement. The transition from the solo practitioner, to large group practices, led to shared call schedules between multiple providers. Increased employment by hospitals or large national provider groups has also contributed to a shifting mentality regarding the doctor-patient relationship. Mergers between healthcare systems and other factors have led to an increasingly mobile physician workforce, further fracturing the long-term relationships between physician and patient. Marketing practices developed by insurance payers have led to patients frequently jumping from plan to plan, and shifting their primary care physician to remain “in-network.” Despite these and other pressures affecting the doctor-patient relationship, the pivotal role of an attending physician remained strong through the early days of the hospitalist movement.

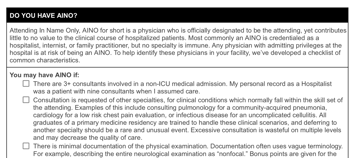

Today, the role of the “attending,” is a far cry from the idealized, traditional model. There is instead, a growing majority of physicians working in the hospital setting, acting as “Attending In Name Only” (AINO). My roles as a Physician Advisor, and a practicing hospitalist have given me a front-row seat during this transition. Working with hospitals from the East Coast to the West Coast and all points between has revealed this to be a national trend, not a local phenomenon.

Sign-up for a detailed checklist to determine if your facility has AINO HERE

There’s a special subset of the AINO, and for lack of a better term, we will refer to this group as an “Involuntary AINO (I-AINO).” These hospital attendings are found wherever practice patterns, contractual obligations, or hospital policy, require a physician to act as the attending, despite having little to no direct involvement in the management. As a hospitalist of 30 years, I can personally speak to the frustration of being forced to act as the I-AINO. The two most common situations involve surgical patients and admissions to the intensive care unit.

As a practice at some hospitals and regardless of the diagnosis, surgical patients are admitted under the hospitalist. There are pros and cons to this approach, And whether the practice meets the criteria for I- AINO, depends on whether there is mutual respect, coordination and collaboration between the specialties. Consider the following:

- When done correctly, the hospitalist-as-attending model adds significant value.

- The hospitalist is more likely to provide detailed documentation regarding the patient’s comorbidities, thereby improving team awareness of the patient’s preoperative risk, and increasing the accuracy of billing.

- The medical attending can be tasked with ensuring that all elements of a National Coverage Determination, or Local Coverage Determination, are present, decreasing the risk of denial from payers due to a “lack of medical necessity.”

- The medical attending may free the surgeon from non-critical responsibilities allowing him/her to be more effective in their primary role as a surgeon.This is especially true in facilities where hospitalists are available 24/7, or when surgical specialties are short-staffed. For example, when I’m admitting a patient requiring orthopedic or neurosurgical intervention at 1 AM, I often half-jokingly explain that my involvement allows the surgeon to rest through the night, and be awake during the operation the next morning.

- Outside of the operating room, the majority of issues fall within the purview of the medical physician, and do not require the surgeon’s involvement. Examples of these include lab abnormalities, pain management, bowel and bladder issues, or management of the patient’s comorbidities such as diabetes.

When done poorly, the hospitalist as I-AINO, can be a nightmare for the patient, nursing, and hospitalist. Many times I’ve been left to discharge a patient, with no communication from the surgeon regarding critical elements such as his/her preferred wound management, weight bearing status, plans for follow-up imaging, removal of sutures, or other aspects of postoperative care. In addition, if the surgeon is a poor communicator, the medical physician often is left trying to muddle through explaining the surgical plan to the patient or family. Even with good communication, there have been a multitude of times where I provided the patient a detailed explanation of the plan given to me by the surgeon, only to be contradicted by the same surgeon a short time later.

The second scenario involves admissions to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Here, the hospitalist or Primary Care Physician (PCP) is assigned as the attending, while the intensivists act as the true attending physician. Again, if structured correctly, there are benefits to this arrangement. More often, the structure is poorly designed, with negative outcomes for the patient, physicians and facility. When structured well, the hospitalist acts as an intermediary and coordinator between the multiple specialties involved in the case. He/she works to ensure that care is timely, appropriate, and length of stay is optimized. The hospitalist may lead discussions with the patient and family, attend family conferences, and clarify the goals of treatment.

- Early involvement ensures that the hospitalist is aware of the patient’s clinical course during most critical aspects of the hospitalization. Once the patient transitions from the ICU to a general medical floor, the hospitalist assumes an increasingly prominent role, and is more effective due to their knowledge of the patient’s hospital course.

Poorly designed or implemented systems lead to confusion as to who is in charge, create conflicting care plans, and inconsistent information provided to the patient and family. I have personally worked in intensive care units as the official attending, only to have the critical care physician yell “don’t touch my patients.” Too often the I-AINO is not an active member participating in the care plan. This is reflected in progress notes that are clones of other clinicians, a copy and paste from previous visits, or add little to no value to the overall patient management. Hospitals in this category typically have chronic issues with excessive Length Of Stay (LOS) in the ICU, excessive testing procedures, and other negative metrics.

So now you SUSPECT that your HOSPITAL has a PROBLEM with AINO physicians. WHAT’S The NEXT step?

There are a multitude of reasons a hospital may be burdened with the AINO. Effective intervention to minimize the negative system effects requires a deep understanding of the health system, and an ability to focus efforts at leverage points that are most likely to lead to positive outcomes.

Solutions may include:

- Review Care Coordination Agreements. Reviewing any care coordination agreements between physician groups such as hospitalists and surgical subspecialists, or the hospitalist role in the intensive care unit, is a good start. Confirm that an agreement is in place, review the document for any gaps in assigning responsibilities to each of the parties, and validate the agreement is appropriately implemented.

- Involve a Seasoned Physician Advisor, or Other Champion. It is beneficial to perform an audit to gain a baseline understanding of the issues. But knowing what to look at, and where to audit, requires experience. Process and system improvement are key roles for the physician advisor. Few clinicians within the health system have a broader understanding of how the hospital is performing, or which solutions are most viable.

- Consider IT and AI Solutions:

- Many of the characteristics listed for an AINO are related to physician charting. Modifications of the EMR may be utilized to minimize some of the worst documentation habits. This includes cloning, cut-and-paste, and “note bloat” (the practice of including extensive amounts of material with little to no immediate value within a progress note).

- AI programs may be utilized to monitor the system more efficiently than is possible with humans, but only if the program is correctly designed to get the desired results. Since no two hospitals have the exact same issues, the baseline audit of current system performance is utilized to identify the most useful metrics for AI monitoring. In addition, general data available to most hospitals can be leveraged to gain insight into the problem areas. One example is identifying the average number of consults ordered by each attending, and then evaluating outliers to determine any opportunities for improvement.

The trends in healthcare are leading to increasing numbers of AINO’s, and if you work within a hospital, there are likely several at your facility. Their negative impact on the health system is not inevitable, and steps can be taken to minimize this impact. Targeted interventions under the guidance of a physician advisor or physician champion can reap positive benefits in terms of patient care, and general hospital performance. For those facilities with a more systemic issue with AINO-like behavior, the interventions are likely to require a data-based solution, EMR modifications, or involvement of an AI program. Contact us for more information and assistance.